About my research

About my research

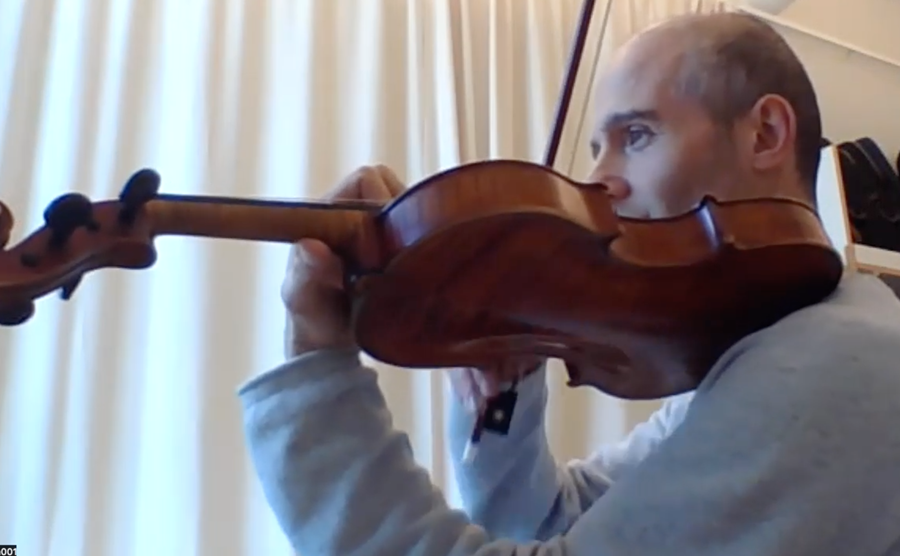

Many great violinists suggest to their students that they should try playing without shoulder rest, suggesting they will get a bigger and more beautiful sound, more physical freedom and better artistic results. But more often than not, they can not really explain HOW to do that, and students return to using the shoulder rest although they would have preferred not to.

How did violinists manage to balance their instrument and perform virtuosic music during the time before the shoulder rest was invented? Paganini for example didn’t use a shoulder rest or a chin rest. Why do we nowadays believe that such virtuosic repertoire is impossible to perform without devices, while the composer himself was able to do that? And how did this balance effect articulation, phrasing, sound production and style? In what ways might modern performers benefit from a better understanding of those practices and how might this be applied to both modern playing as well as in contexts of historically-informed performance?

Survey

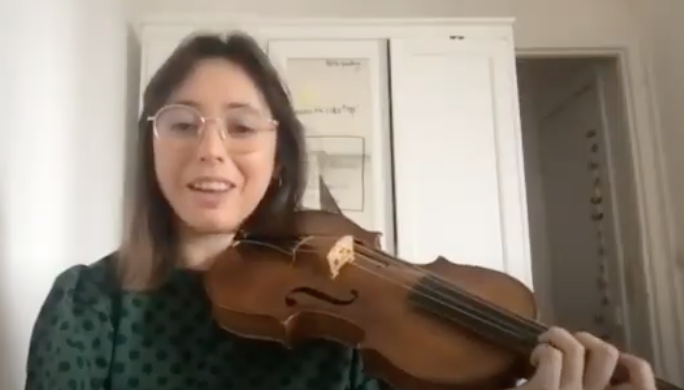

To prepare the experiment I performed a preliminary survey about equipment choices and ways of supporting the instrument, to be seen here. Around 413 violinists / viola players from all over the world took part in it. From these participants, 42% of their concerts takes place on period instruments. 63% is using a shoulder rest, 11% only a chin rest, 10% neither chin nor shoulder rest, 14% depending on the repertoire they play. The most interesting outcome was that a lot of them considered it impossible to perform Paganini either without shoulder rest or without shoulder and chin rest. Many people who filled out the survey would be interested to learn to play without these devices.

Quote from Menuhin

In his book “Six lessons with Yehudi Menuhin” he writes about balancing the violin: “We speak of holding the violin, but the word ‘hold’, with its implication of a firm and static grip, can be misleading. We should remember that the violinist, unlike the pianist or cellist whose instruments rest on the floor, must support his instrument unaided… Here, as with the bow, the development of a sense of balance and flexibility will form a far freer and healthier basis on which later to apply strength and effort, than would clamping the violin between shoulder and head, or clutching it between the thumb and first finger of the left hand… It is preferable to do without a shoulder-pad or a shoulder-rest. If used as a support, the shoulder is restricted in its freedom of movement, and if actively ‘clamped’, the shoulder is ‘frozen’.” As an Alexander Technique teacher I very much agree with this. The question remains: How to develop this balance and flexibility, and how to teach it to others?

My research

Part 1 of my research is a historical narrative about violin support, throughout Europe: starting from playing without anything; the development of the chin rest; the development of the shoulder rest and the reasons why. Including a chapter on conservatoires and their influence in this. How did these ways of supporting the instrument influence for example articulation, portamento and vibrato. HIP players can draw conclusions from this.

Part 2 of my research is about the question: What (if anything) can the modern player learn from these historical examples? In this part the experiment I am planning to perform (see next page) will be very important, to measure how easy or difficult people find it to change their technique and to experiment with different ways to teach these skills. And most important: How much musical and technical result can be booked over 3 months time and how happy are the musicians with the result? Does the playing get easier, freer and more beautiful?

More information:

- Alexander Technique practice by Esther Visser (www.free-up.nl)

- Video on Alexander Technique in performing arts (youtube)

- The Performing Self project (www.performingself.org.uk)